It All Starts with a Conversation

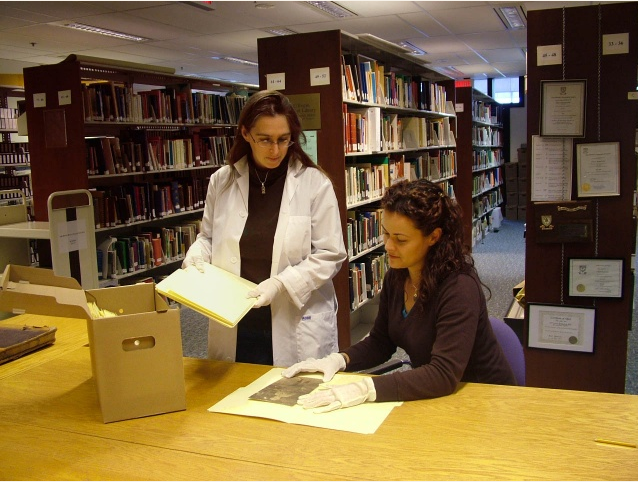

When work on a Bookhouse Group commemorative book project begins, one of the most important decisions we make is who will be the writer of the book.

The writer isn’t just a wordsmith, hired to communicate a client’s story effectively. The writer acts as an all-important guide who shepherds our client through the process of telling their story. At Bookhouse, we feel that a writer’s job is to become immersed deeply in the culture of the company that is being celebrated—to understand the relationships within the organization that make it unique and ultimately lead to the company’s success. In other words, to appreciate its people.

I work as a project manager for Bookhouse, but occasionally I have served as a writer for our clients—an eclectic clientele such as churches, hoteliers, construction companies, educational institutions, cities, and cultural arts organizations, among others. Early in my career, I found that tackling such diverse projects was a bit daunting (I can put together IKEA furniture, but what do I know about constructing a skyscraper?!). I’ve since realized that the key to telling these important stories is simple—conducting interviews. Lots and lots of interviews with lots of key players.

The problem: Most managers and employees I ask to speak might be reluctant to talk to me because (1) I’m an unknown quantity and (2) they’re busy people without a lot of time to spare. A majority of them might have only experienced an interview in one setting—sitting opposite an employer or client they’re hoping to impress—a stressful experience that most would rather avoid.

So, I make it my mission to quickly set folks at ease and create an atmosphere where they can be comfortable. A vast amount of background research and a sense of humor come in handy to set the tone for these discussions. After a few minutes, I find that people relax and we’re chatting like we’ve known each other for years.

Our philosophy at Bookhouse is that this is the best way to truly tell the story of what makes a company tick, how it came to be, where it wants to go. The people who’ve made it happen have stories that are pieces in a large puzzle, and a talented writer puts those pieces together to create an engaging story. We weave the information we glean from interviewing owners, managers, employees, customers, and even vendors in order to document our clients’ history. We engage the reader with an insightful and entertaining story describing how each company overcame challenges, met with struggles and turned them into successes, and now will look into a crystal ball to predict a bright future.

It all boils down to the art of conversation—something we’re pretty good at.

—Stacy Moser, Project Manager

Contact us about telling your story.